A Ban on Banks: Wisconsin’s Radical 1846 Constitution

Political leaders have been debating for months over how to deal with the banking-induced financial crisis currently seizing the world, but controversy over banking is nothing new. Wisconsin’s history demonstrates this vividly. In 1846, as Wisconsin was preparing for statehood, a political convention met in Madison to author the state constitution. The draft this convention created never took effect—citizens overwhelmingly rejected it in an 1847 referendum, and statehood was delayed until a second constitution was approved the next year. The first proposal, voters thought, was simply too radical. Two of its radical provisions dealt with debt and banking.

One section of the rejected constitution, the Homestead Provision, was designed to protect family homes from being seized to cover debt. An even more radical proposal, Article 10, actually banned any bank from doing business within Wisconsin’s borders.

The Homestead Provision, based on provisions in the earlier Texas Constitution, would have exempted the family home and forty acres, to a maximum value of one thousand dollars (then a substantial sum), from being seized to repay contractual debts. The second constitution replaced this with a more vague statement exempting only “a reasonable amount of property” from seizure. Currently, Wisconsin law provides an exemption for property worth up to $40,000, but it does not apply to mortgages or debts incurred to purchase or improve the home.

The idea to forbid banking in Wisconsin was proposed by Edward G. Ryan, a Democrat elected to the constitutional convention from Racine. The convention approved his proposal by a 79-27 vote, and the article they passed read like this:

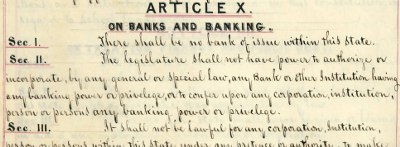

Article X: On Banks and Banking

Section I: There shall be no bank of issue within this state.

Section II: The legislature shall not have power to authorize or incorporate, by any general or special law, any bank or other institution having any banking power or privilege, or to confer upon any corporation, institution, person or persons any banking power or privilege.

Section III: It shall not be lawful for any corporation, institution, person or persons within this state, under any pretense or authority, to make or issue any paper money, note, bill, certificate, or other evidence of debt whatever intended to circulate as money.

Section IV: It shall not be lawful for any corporation within this state under any pretense or authority, to exercise the business of receiving deposits of money, making discounts, or buying or selling bills of exchange, or to do any other banking business whatever.

Section V: No branch or agency of any bank or banking institution of the United States, or of any State or Territory within or without the United States shall be established or maintained within this state.

Section VI: It shall not be lawful to circulate within this state, after the year one thousand eight hundred and forty seven, any paper money, note, bill, certificate or other evidence of debt whatever intended to circulate as money, issued without this state, of any denomination less than ten dollars, or after the year one thousand eight hundred and forty nine, of any denomination less than twenty dollars.

Section VII: The legislature shall, at its first session after the adoption of this constitution, and from time to time thereafter as may be necessary, enact adequate penalties for the punishment of all violations and evasions of the provisions of this article.1

Wisconsin’s politicians were willing to ban banking because they had lived through decades of bank-related economic turmoil. In 1816, the U.S. Congress had delegated management of federal finance to a private corporation, the Second Bank of the United States, but in 1819 and 1834, the bank’s policies were blamed for causing recessions. The congressional charter for the bank expired in 1836, but in its stead, unregulated “wildcat banks” began offering easy loans and printing money, as was legal at the time. Eager for profit, the banks expanded rapidly, making too much money available far too quickly. The resulting inflation triggered a depression that lasted from 1837 to 1843, unparalleled in severity until the Great Depression. When Wisconsin’s founding politicians met to write the constitution in 1846, these events were still fresh in mind.