An Old Idea: Wisconsin and its University

This September marks the beginning of fall term for more than 180,000 students across the twenty-six campuses of the University of Wisconsin System. The return to school is an opportunity for reunion and renewal, for the discovery of new possibilities and the re-evaluation of old ideas — including the idea of public higher education itself. If this idea is to remain relevant in the years to come, then we must value public universities as something more than a monetary cost to taxpayers and a dollar discount to tuition payers. At the foundation of any real public state university there is a deeper value: service and accountability to the people who make up the state. One need not look farther than the development of the University of Wisconsin itself for an illustration of what this ideal means.

The University of Wisconsin and the State of Wisconsin were created in the same stroke. Article 10, Section 6 of the Wisconsin Constitution of 1848 declared:

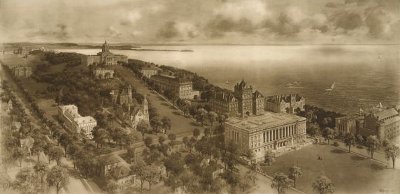

“Provision shall be made by law for the establishment of a state university, at or near the seat of government, and for connecting with the same, from time to time, such colleges in different parts of the state, as the interests of education may require.”

Wisconsin’s founders called for a public university in the state constitution, and established the seat of learning as one with the seat of law, because they had an ideal of cultivating productive citizens, and educated citizens, and cultured citizens, but above all else, citizens — participants in a democracy and shapers of law, not mere subjects either of crown or wealth. John Lathrop, the first UW Chancellor, expressed this concept eloquently at his inaugural address on January 16, 1850:

“The American mind has grasped the idea, and will not let it go, that the whole property of the state, whether in common or in severalty, is holden subject to the sacred trust of providing for the education of every child of the state. Without the adoption of this system, as the most potent compensation of the aristocratic tendencies of hereditary wealth, the boasted political equality of which we dream is but a pleasing illusion. Knowledge is the great leveler. It is the true democracy. It levels up—it does not level down.”1

As it grew, the University of Wisconsin only strengthened in its commitment to knowledge as true democracy. In 1894, when economics professor Richard T. Ely was attacked by in the national press as an anarchist and socialist radical for his research interest in the growing labor movement, the UW Board of Regents convened hearings to investigate, and concluded them by issuing a famous defense of the professor and the freedom to pursue knowledge:

“We cannot for a moment believe that knowledge has reached its final goal, or that the present condition of society is perfect. We must therefore welcome from our teachers such discussions as shall suggest the means and prepare the way by which knowledge may be extended, present evils be removed and others prevented. We feel that we would be unworthy of the position we hold if we did not believe in progress in all departments of knowledge. In all lines of academic investigation it is of the utmost importance that the investigator should be absolutely free to follow the indications of truth wherever they may lead. Whatever may be the limitations which trammel inquiry elsewhere we believe the great state University of Wisconsin should ever encourage that continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found.”2

Some twenty years after the regents made this proclamation, their “sifting and winnowing” statement was affixed in bronze to University Hall (since renamed for UW President John Bascom), becoming an enduring reminder of the commitment to truth.

In the meantime, the University of Wisconsin had begun to redefine the ways in which knowledge could be disseminated and truth be put to the service of democracy. Under the leadership of Charles Richard Van Hise, UW President from 1903 to 1918, the university advocated what became known around the United States as the Wisconsin Idea: a notion often summarized in the slogan “the boundaries of the campus are the boundaries of the state,” meaning that the role of the public university should be public service to all the people of the state and their government — not only the researchers and students on campus. Theodore Roosevelt remarked on this ideal that:

“In no other State in the Union has any university done the same work for the community that has been done in Wisconsin by the University of Wisconsin. … I found the President and the teaching body of the University accepting as a matter of course the view that their duties were imperfectly performed unless they were performed with an eye to the direct benefit of the people of the State; and I found the leaders of political life, so far from adopting the cheap and foolish cynicism of attitude taken by too many politicians toward men of academic training, turning, equally as a matter of course, toward the faculty of the University for the most practical and efficient aid in helping them realize their schemes for social and civic betterment.”3

The “work for the community” that Roosevelt observed one hundred years ago had a wide scope. Sure, the University of Wisconsin at the dawn of the 20th century offered tuition-free admission to Wisconsin residents, paid for by state taxpayers and federal grants — but this was only typical for a public university of the period. What set Wisconsin apart were the university’s efforts to reach beyond traditional student instruction to improve life across the state.