An Old Idea: Wisconsin and its University

This September marks the beginning of fall term for more than 180,000 students across the twenty-six campuses of the University of Wisconsin System. The return to school is an opportunity for reunion and renewal, for the discovery of new possibilities and the re-evaluation of old ideas — including the idea of public higher education itself. If this idea is to remain relevant in the years to come, then we must value public universities as something more than a monetary cost to taxpayers and a dollar discount to tuition payers. At the foundation of any real public state university there is a deeper value: service and accountability to the people who make up the state. One need not look farther than the development of the University of Wisconsin itself for an illustration of what this ideal means.

The University of Wisconsin and the State of Wisconsin were created in the same stroke. Article 10, Section 6 of the Wisconsin Constitution of 1848 declared:

“Provision shall be made by law for the establishment of a state university, at or near the seat of government, and for connecting with the same, from time to time, such colleges in different parts of the state, as the interests of education may require.”

Wisconsin’s founders called for a public university in the state constitution, and established the seat of learning as one with the seat of law, because they had an ideal of cultivating productive citizens, and educated citizens, and cultured citizens, but above all else, citizens — participants in a democracy and shapers of law, not mere subjects either of crown or wealth. John Lathrop, the first UW Chancellor, expressed this concept eloquently at his inaugural address on January 16, 1850:

“The American mind has grasped the idea, and will not let it go, that the whole property of the state, whether in common or in severalty, is holden subject to the sacred trust of providing for the education of every child of the state. Without the adoption of this system, as the most potent compensation of the aristocratic tendencies of hereditary wealth, the boasted political equality of which we dream is but a pleasing illusion. Knowledge is the great leveler. It is the true democracy. It levels up—it does not level down.”1

As it grew, the University of Wisconsin only strengthened in its commitment to knowledge as true democracy. In 1894, when economics professor Richard T. Ely was attacked by in the national press as an anarchist and socialist radical for his research interest in the growing labor movement, the UW Board of Regents convened hearings to investigate, and concluded them by issuing a famous defense of the professor and the freedom to pursue knowledge:

“We cannot for a moment believe that knowledge has reached its final goal, or that the present condition of society is perfect. We must therefore welcome from our teachers such discussions as shall suggest the means and prepare the way by which knowledge may be extended, present evils be removed and others prevented. We feel that we would be unworthy of the position we hold if we did not believe in progress in all departments of knowledge. In all lines of academic investigation it is of the utmost importance that the investigator should be absolutely free to follow the indications of truth wherever they may lead. Whatever may be the limitations which trammel inquiry elsewhere we believe the great state University of Wisconsin should ever encourage that continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found.”2

Some twenty years after the regents made this proclamation, their “sifting and winnowing” statement was affixed in bronze to University Hall (since renamed for UW President John Bascom), becoming an enduring reminder of the commitment to truth.

In the meantime, the University of Wisconsin had begun to redefine the ways in which knowledge could be disseminated and truth be put to the service of democracy. Under the leadership of Charles Richard Van Hise, UW President from 1903 to 1918, the university advocated what became known around the United States as the Wisconsin Idea: a notion often summarized in the slogan “the boundaries of the campus are the boundaries of the state,” meaning that the role of the public university should be public service to all the people of the state and their government — not only the researchers and students on campus. Theodore Roosevelt remarked on this ideal that:

“In no other State in the Union has any university done the same work for the community that has been done in Wisconsin by the University of Wisconsin. … I found the President and the teaching body of the University accepting as a matter of course the view that their duties were imperfectly performed unless they were performed with an eye to the direct benefit of the people of the State; and I found the leaders of political life, so far from adopting the cheap and foolish cynicism of attitude taken by too many politicians toward men of academic training, turning, equally as a matter of course, toward the faculty of the University for the most practical and efficient aid in helping them realize their schemes for social and civic betterment.”3

The “work for the community” that Roosevelt observed one hundred years ago had a wide scope. Sure, the University of Wisconsin at the dawn of the 20th century offered tuition-free admission to Wisconsin residents, paid for by state taxpayers and federal grants — but this was only typical for a public university of the period. What set Wisconsin apart were the university’s efforts to reach beyond traditional student instruction to improve life across the state.

For those who could not dedicate their time to a four year degree program, the university offered free week or month long short courses on practical farming and mechanical techniques, preparing citizens with the skills needed to succeed in the early 20th century workplace. For those who could not afford the trip to Madison, the university launched mail-correspondence courses on all manner of subjects, published educational pamphlets for mass distribution, and most crucially, sent university faculty around the state to follow up on correspondence, answer questions, and explain complex research findings in person. At the same time, professors could connect with citizens to gain a sense of the real world problems affecting people around Wisconsin. In the words of UW President Van Hise:

“We would like to have the university reach all the people of the state. There is no reason, that I can see, why our resources for knowledge, training and experiment, should not be thrown open to everyone. We are beginning to think about the conservation of the natural resources of the country; why not conserve also the human resources? This can be done by giving everybody an equal opportunity to discover and develop his highest efficiency, and it would save to the state all special talent.”4

Public service did not end at public instruction. In their libraries and laboratories, university faculty labored at research that could solve the everyday problems facing Wisconsin citizens. Most memorably, in 1890, Professor Stephen Babcock created a process to test the amount butterfat in milk, a simple figure that had huge implications for the nascent dairy processing industry in Wisconsin. Instead of patenting his method, Babcock described to the public in a university bulletin so that farmers and creameries could immediately begin using the test, helping to pave the way for Wisconsin to become “America’s Dairyland.” The increased production of butter resulting from the Babcock Test increased the state’s annual dairy output by $800,000 in an era when the university’s annual budget was less than half that figure5 — and the butterfat test was just one among many research findings improving the value of the state’s biggest business, agriculture.

Scholars at the University of Wisconsin also directed their research findings at improving society and government, offering expert knowledge to the lawmakers gathered at the opposite end of State Street. Charles McCarthy, a graduate student in history at UW from 1898 to 1901, went from the university to establish the state’s Legislative Reference Library, which offered legal drafting and research assistance to elected officials, connecting lawmakers with experts in their field from the university. Robert M. La Follette, Governor of Wisconsin from 1901 to 1906, wrote:

“I made it a further policy, in order to bring all the reserves of knowledge and inspiration of the university more fully to the service of the people, to appoint experts from the university wherever possible upon the important boards of the state — the civil service commission, the railroad commission and so on — a relationship which the university has always encouraged and by which the state has greatly profited.”6

Such appointments by La Follette and the succeeding Republican Governors James Davidson and Francis McGovern gave University of Wisconsin professors such as John Commons the opportunity to apply scientific solutions to social problems and shape legislation on workplace safety, injury compensation, and child labor, among other things. La Follette called regular meetings between lawmakers and professors “a tremendous force in bringing about intelligent democratic government.”7

The University of Wisconsin’s success at providing practical solutions to problems of farms, factories, and government did not mean that the institution ignored basic or theoretical research — something that President Van Hise defended vigorously — and its offering of short courses on farming and machine work did not transform the university into a technical school. To the contrary, the connections fostered between chemists and farm students, or economists and legislators, offered researchers who might have been only interested in pure science the insight necessary to see practical applications for their work. Likewise, technical short courses drew workers to campus and provided exposure to the full offerings of the university, from the very latest scientific knowledge to the most cherished classics. It is little wonder that even Charles William Eliot, President of Harvard from 1869 to 1909, called the University of Wisconsin “the leading state university.”8

In the words of muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens, who wrote a feature on the school for American Magazine in 1909, the University of Wisconsin’s programs were “Sending a State to College.” The combination of basic and applied research, practical and theoretical instruction, proved the value of the school to both government and the people, and it made the university more truly universal in the scope of knowledge that it could sow and cultivate. It was a campus where students of the agricultural short course joined debating clubs to think critically over the political issues of the day, so much so that the growing UW Extension program published bulletins advising readers across the state on how they could organize debating societies in their hometowns and choose relevant political questions for argument. The University of Wisconsin sought to give every worker and farmer the education befitting a citizen.9

What has become of the public service ideal that guided the university from its foundation? There has been new progress over the years: the contribution of UW researchers like Edwin Witte and Arthur J. Altmeyer to Federal New Deal legislation, for example, or the creation of the modern University of Wisconsin System in 1971 to link students and scholars with resources from campuses in every corner of the state, from Superior to Parkside. Meanwhile, however, something has gone out of the university: it is no longer as connected, somehow, to the people off campus who make up the state. The renewed emphasis on basic research from the mid-20th century onward has led to a decline in applied science that the public can immediately seize for benefit. The acceleration of specialization and the fragmentation of departments has led to ground breaking discoveries, but isolated professors from society in an Ivory Tower of Babel — magnificent but wrecked by layers of jargon no one can understand.

For all the brilliance of its research, a public university must be able to communicate its work, not merely to its students, but to its public, to its state, to at once demonstrate and live up to its value. It is deeply troubling that so many inside the University of Wisconsin System see such public service as burdensome, and seek openly in plans like the Wisconsin Idea Partnership or the New Badger Partnership to make the university only more autonomous from the state and the people. Today UW-Madison’s website for the Wisconsin Idea proclaims that its “academic programs are constantly adapting to meet the needs of state business and industry” — an critical mission — but the site says nothing about serving the needs of democracy.

It would be wrong to lay all the blame for this change on the university, however. Already the State of Wisconsin has fallen so behind on funding for the UW System that the state today provides only about 21% of the system’s operational budget. Why should the universities bother to serve the people if the people’s representatives refuse to support the universities’ needs? The UW System takes in more from student fees, grants, and private contracts than it does from taxpayers, and financially, therefore, its accountability must be more to the former group than the latter. Who gains from this? Far from the cost-free tuition of the early 20th century, today 71% of undergraduates must take on debt to afford their public education, and the average debt of borrowers in the UW System is more than $25,000.10 So much, alas, for Chancellor Lathrop’s potent compensation for the aristocratic tendencies of wealth.

We must, for the sake of our future, value our public universities as something more than items in a state budget or simply schools that receive public funds. Funding, certainly, is a critical tool to promote public education, but the difference between a private and a public university is more than where the money comes from: it is at its truest a difference in meaning and in mission. Private universities offer wonderful opportunities that give them an important role in our society, but state universities are something separate, something worth defending forever for the public service they exist to provide. It is up to us, as citizens and stewards of these institutions, to ensure that our university, the University of Wisconsin — meaning all 26 campuses that share that name today, and the extension — remain as Robert La Follette described the UW in 1913: “a great democratic institution — a place of free thought, free investigation, free speech, and of constant and unremitting service to the people who give it life.“11

References:

- Inauguration of Hon. John H. Lathrop, LL. D., Chancellor of the University of Wisconsin, At The Capitol, Madison, January 16, 1850. (Milwaukee: Sentinel and Gazette Power Press Print, 1850), p 42.

- Quoted in Theodore Herfurth, Sifting and winnowing : a chapter in the history of academic freedom at the University of Wisconsin, (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1949).

- Theodore Roosevelt, “Wisconsin: An Object Lesson for the Rest of the Union,” The Outlook v.98 no.4 (27 May 1911), pp 143-145.

- Quoted in Lincoln Steffens, “Sending a State to College: What the University of Wisconsin Is Doing For Its People,” The American Magazine v.67 no.4 (February 1909), p 360.

- Jack Stark, “The Wisconsin Idea: The University’s Service to the State” in The State of Wisconsin Blue Book, 1995-1996. (Madison: Legislative Reference Bureau, 1995), p 37.

- Robert M. La Follette, La Follette’s Autobiography: A Personal Narrative of Political Experiences, (Madison: The Robert M. La Follette Co., 1913), p 31.

- La Follette, p 32.

- Quoted in Steffens, p 350.

- Lincoln Steffens, “Sending a State to College: What the University of Wisconsin Is Doing For Its People,” The American Magazine v.67 no.4 (February 1909), pp 349-364.

- University of Wisconsin System Fact Book 10-11: A Reference Guide to University of Wisconsin System Statistics and General Information. Online at http://www.wisconsin.edu/cert/publicat/factbook.pdf

- La Follette, p 33.

No Responses to "An Old Idea: Wisconsin and its University":

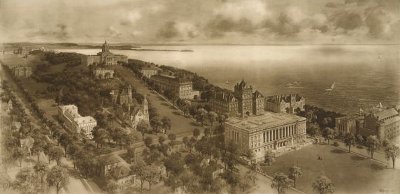

I have a photogravure by A W Elson & Co, N Y that measures about 20X33 of the 1907 version by H D Nichols of The University of Wisconsin.

I rescued it from a school building storage room that was being torn down and was going to be thrown away.

Could you tell me if it has any value other than sentimental value? It is not torn and it’s in an oak frame with the original glass. It is dirty from being stored in a closet.

Any information would be appreciated. Thank you, Warren