Marquette and Jolliet: 350 Years of Changing Evaluations

Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet are celebrities of Midwestern history. Cities and schools are named in their honor and their likenesses appear in art and architecture around the United States. This year marks the 350th anniversary of the event for which Marquette and Jolliet are famous: a canoe voyage down the Mississippi River with five voyageurs in 1673. The anniversary is being widely publicized. My hometown of Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, near where the French first entered the Mississippi, is celebrating the event with a carnival. From these commemorations, it might seem that Marquette and Jolliet have always been figures of great historical importance — but the cultural significance of their canoe trip has shifted greatly over the last three and half centuries.

The Debated Claim of “Discovery”

Like other children in my predominantly white hometown, I was told while growing up that Marquette and Jolliet were important because they “discovered” the Mississippi River in 1673. Already by high school, I learned that this was not quite accurate — but not because it neglected the Indigenous nations who had already known the Mississippi for thousands of years. Instead, I learned that the Spaniard Hernando De Soto had “discovered” the Lower Mississippi in 1541, and that other French men, such as Radisson and Groseilliers, had perhaps already seen the Upper Mississippi in the 1650s. Regardless, Marquette and Jolliet were to be commended for making the first written account of the river’s course.

Only as a college undergraduate did I read Marquette’s journal and begin to understand that Marquette and Jolliet were guided and supplied by Native American allies on their journey, traveling water routes that were long established by Menominee, Illiniwek, Quapaw, and other Indigenous nations. Marquette’s account of the voyage makes clear that the travelers not only relied on Indigenous knowledge, but also saw meeting with the people who lived along the Mississippi as the main purpose of their journey. They did not set out to map an empty land — in fact, they set out with a map already started based on reports from Illiniwek people. Marquette and Jolliet traveled to lands that they knew were inhabited because they sought to draw new people into the colonial orbit of France and the Catholic Church. Meeting people was so central to the journey that Marquette could write that the expedition “advanced over 60 leagues since we entered the river, without discovering anything” — until they finally reached the Peoria village of the Illiniwek a week after entering the Mississippi.

Today’s media reports on the 350th anniversary of Marquette and Jolliet’s voyage are making an overdue effort to recognize the centrality of Indigenous people in the expedition, as well as the legacy that the journey had in furthering the European colonization of Indigenous homelands. As Indigenous studies professor Margaret Huettl explained in a discussion with Wisconsin Public Radio, the explorers traveled through “a thriving network of Indigenous economies, politics, and social communities.” Children today hopefully don’t have to reach college before understanding that the 1673 expedition was a meeting of cultures where Europeans followed in the footsteps of Indigenous guides rather than treading new, unbroken ground. At the same time, in commemorating the explorers, today’s reports still dance awkwardly around the notion of “discovery,” acknowledging that the word is misplaced, but struggling to articulate an alternative reason for Marquette and Jolliet’s ongoing significance.

This month’s Wisconsin State Journal, for example, aimed to recognize Indigenous contributions to the 1673 voyage but still quoted the Wisconsin Historical Society describing an expedition “that introduced Christianity into 600,000 square miles of wilderness.” Any such “wilderness” is a modern fiction contradicted by the explorers’ original version of events. Jolliet wrote in a letter after the trip that “I noticed on our route more than 80 villages of Indians, each of 60 to 100 houses, and even one of 300 … Several of these nations plant crops three times a year.” This was not a wilderness, but a populous and cultivated landscape.

Viewing the earliest texts about the 1673 expedition, it is apparent that the voyage did not have quite the same significance at the time as it does today. The explorers understood themselves to be “discovering” people and places that had not yet been mapped by the French, but they wrote about their journey in a matter-of-fact way, as sightseers on a river peopled by Indigenous nations and, they suspected, Spanish colonists. Indeed, Marquette and Jolliet cut their trip short and turned around before reaching the mouth of the Mississippi because they worried that they would otherwise “fling ourselves into the hands of the Spaniards,” who they feared far more than the hospitable Native people they met. The expedition was thus only a tentative and partial success. As the forward to Joseph Donnelly’s biography of Jacques Marquette states, “In his brief life he was unhonored and unapplauded. … It is certain that he himself did not realize the importance of what he had accomplished.” This importance was only bestowed by later generations.

Marquette and Jolliet in French History

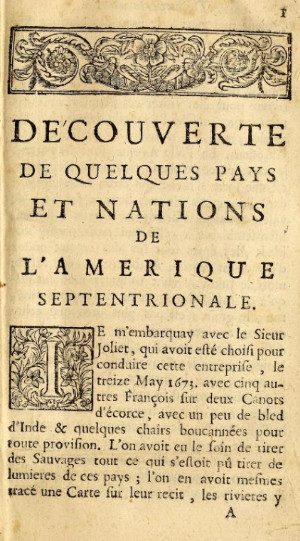

Marquette’s account of the 1673 expedition was first published in Europe in 1681, a few years after the Jesuit missionary died on a return visit to Illinois. The narrative appeared only in an abridged form, as one of several travel narratives in Melchisédec Thévenot’s book Recueil de voyages. The section containing Marquette’s narrative carried the title “Decouverte de quelques pays et nations de l’amerique septentrionale” (“Discovery of some countries and nations of North America”). With this announcement of discovery, the title reflects its European perspective, but it also underscored that existing nations and people were at the center of Marquette’s journey. French colonialism in this period relied on incorporating new people into the empire. This form of colonialism imposed a hierarchy that aimed to claim Native people and lands as objects of European discovery, but it did not aim to displace and erase Indigenous societies in the way that English and later American settler colonialism would.

Despite its publication, the Marquette narrative was quickly overshadowed in Europe by other stories of colonial adventures. In the late 1670s, René-Robert Cavelier Sieur de La Salle and Louis Hennepin continued the French exploration of the Mississippi River, which La Salle claimed for France as the colony of Louisiana. By 1683, Hennepin published the Description de la Louisiane with an exaggerated account of his travels. Hennepin sought to take credit for French exploration and downplayed or ignored the role of other travelers. He also portrayed the Indigenous people of the Mississippi Valley in a far more hostile light than Marquette’s account. Perhaps because of its dramatic embellishment, Hennepin’s narrative attracted more readers than Marquette’s writing, and it was quickly translated into English and other European languages. Although some of Hennepin’s European publishers attached a condensed account of Marquette and Jolliet’s expedition to their editions of Hennepin’s narrative, the earlier voyage was consigned to the appendix if it was included at all. For a time, the 1673 expedition seemed destined for obscurity, even as France began to establish its first colonial settlements along the Mississippi.

The French Jesuit Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix brought attention back to Marquette and Jolliet in the 1740s when he wrote Histoire et Description Generale de la Nouvelle France. This multi-volume work was the most complete history of French North America published up to the time. Charlevoix understandably took an interest in the story of Father Marquette, a fellow Jesuit, and gave him credit, along with Jolliet, for “discovering” the Mississippi River.

Although Charlevoix’s history was influential in France, it did not quite ensure the explorers a lasting renown. In the mid-eighteenth century, Britain defeated France in the Seven Years War. As a result, France lost its colonial claims to the Mississippi River basin, dividing them between Britain and Spain. These empires had little interest in memorializing their French rivals. In addition, the Society of Jesus had become embroiled in religious and political disputes that made the Jesuits unpopular, leading to their suppression and expulsion from the Americas. Even in France at this time there was little interest in celebrating the history of Jesuit priests like Charlevoix and Marquette. The French Enlightenment sought to secularize knowledge outside control of the church, and in the 1760s, the famous French Encyclopédie edited by Diderot and D’Alembert gave credit for discovery of the Mississippi to the Spaniard Hernando De Soto. The Encyclopédie mentioned Marquette and Jolliet in two articles by Louis de Jaucourt on the Mississippi River and Louisiana, but with no special prominence, noting them simply as the first in a series of French explorers, along with La Salle, Hennepin, and D’Iberville.

Fame in Nineteenth Century America

Only after the 1830s did Marquette and Jolliet inspire statues and paintings and become the namesake for cities and schools. Two factors brought about their unprecedented celebrity status during the nineteenth century.

In the first place, the arrival of American settlers in the Western Great Lakes and Upper Mississippi Valley prompted a search for origin stories that tied this unfamiliar landscape to European “civilization.” In the 1840s, the American settlements of Joliet, Illinois, and Marquette, Michigan, were among the first to take their names from the explorers. Around the same time, early American historians like George Bancroft recognized that Marquette’s narrative was the oldest available European account of places like the rising settlements of Chicago and St. Louis, and they used the 1673 expedition to open histories of what became the Midwestern region of the United States. In these narratives, Marquette and Jolliet’s travel took on a new meaning. They were no longer portrayed primarily as travelers through an Indigenous world, but as the first pioneers who opened a new world destined for European settlement. In such nineteenth century histories, the 1673 expedition was the first step in a history of “progress” that culminated in the violent removal of Indigenous people and the flourishing of U.S. settler society.

The second factor that led to a revival of interest in Marquette and Jolliet was the arrival of Catholic immigrants and the return of the Jesuit order to North America, which led to the foundation of schools and scholarly communities interested in preserving Catholic history. In 1844, the Jesuit Felix Martin rediscovered the original manuscript of Marquette’s travel narrative in the archives of a Quebec hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu. The manuscript provided a more complete account of the 1673 expedition than had previously been published. This rediscovery stimulated new scholarship such as Catholic historian George Shea’s 1852 book, Discovery and Exploration of the Mississippi Valley. As the Jesuits founded new schools and churches across the United States, they seized on the Marquette story to claim one of their own among America’s founding figures. In addition to Marquette University, founded in Milwaukee in 1881, the Jesuits also named campus buildings and commissioned artworks of Marquette at other schools such as Campion in Prairie du Chien and Loyola (my own graduate school) in Chicago.

Marquette reached the apex of his fame at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1895, the Marquette Building, an early Chicago skyscraper, commemorated the explorer with bronze relief sculptures and tile mosaics. The next year, in 1896, the state of Wisconsin donated a marble statue of Marquette as one of two figures to represent the state in the National Statuary Hall inside the U.S. Capitol. The statue was not without controversy, as anti-Catholic organizations like the “American Protective Association” protested the representation of a Jesuit at the seat of American Government. Public Opinion, a weekly magazine of the time, noted that “Owing to threats of violence to the Marquette statue, policemen in citizens’ garb guard it day and night.” The opponents of Marquette failed to win enough backers to have the statue removed, however. “We in the Northwest consider Marquette a Christian hero, whether a Jesuit or not,” wrote G. Mott Williams, an Episcopalian bishop in Marquette, Michigan.

By 1902, historian Reuben G. Thwaites of the Wisconsin Historical Society published the first book-length biography of Marquette, providing a scholarly history to accompany the explorer’s celebrated public image. Like other commemorations of this period, Thwaites held up Marquette as a founding figure for a triumphal history of American settler colonialism, but this history relied on a racist belittling of the contributions of Indigenous people. “Father Marquette was great as an explorer, as a tamer of savages, as a preacher…” Thwaites wrote, adding that “We may … properly claim him as an American hero.”

The Last Hundred Years

Marquette and Jolliet’s late rise to fame began to attract suspicion among some scholars as the twentieth century progressed. Perhaps, they suggested, the duo’s importance had become exaggerated. Francis B. Steck, a Franciscan priest and historian, led this critical charge. In 1927, Steck published The Jolliet-Marquette expedition, 1673, in which he argued not only that it was improper to credit Marquette and Jolliet with the “discovery” of the Mississippi given previous Spanish exploration, but also that Jesuits had over-inflated Marquette’s role in the expedition and given him credit for work that was really led by Jolliet. Steck continued research aimed at discrediting Marquette for several years, culminating in his book Marquette Legends in 1959, which compiled evidence that Marquette’s travel narrative was a sophisticated forgery and suggested that the Jesuit may never have even participated in the 1673 expedition with Jolliet.

Steck’s arguments against Marquette attracted serious attention, but they haven’t stood up to detailed scrutiny. Subsequent studies by Joseph Donnelly, Raphael Hamilton, and David Buisseret and Carl Kupfer have reasserted the authenticity of Marquette’s narrative through a detailed examination of manuscript sources in Canada and France. Already by the later twentieth century, however, the popular importance of the seventeenth century explorers was in decline. The Civil Rights movement and American Indian Movement put a spotlight on the violent consequences of colonialism in dispossessing Native people and creating racial inequalities that persisted into the present. In this context, the settler triumphalism that had made Marquette and Jolliet so popular in the nineteenth century finally began to lose its appeal. Historians increasingly looked to write narratives that moved beyond the lives of a small number of heroic figures like Marquette and Jolliet to include broader representations of society.

Today, in the twenty-first century, the legacy of the Marquette and Jolliet expedition remains contested. While some places, like Prairie du Chien, are celebrating the 350th anniversary, other cities along the route, like Chicago, are considering the removal of public monuments to the explorers. Last year, even Marquette University reevaluated its commemoration of its namesake, redesigning the university seal to remove an image of Marquette and his Indigenous guide because it perpetuated the stereotypes of its 19th century artist. These reevaluations are nothing new — they are merely the latest turn in a centuries-long saga of changing meanings, as each generation brings new questions and concerns to its interpretation of the Marquette and Jolliet story. Discarding the settler-colonial bias of nineteenth century depictions and recognizing the original centrality of Indigenous people in the 1673 expedition is a welcome change to the way Americans remember this historic encounter.

Bibliography

The following sources provided information for this article and offer more details about the history and memory of Marquette and Jolliet

- Chmielewski, Laura M. Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet: Exploration, Encounter and the French New World. Routledge Historical Americans. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018.

- Hamilton, Raphael N. Marquette’s Explorations: The Narratives Reexamined. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1970.

- Kupfer, Carl, and David Buisseret. “Validating the 1673 ‘Marquette Map.’” Journal of Illinois History 14 (2011): 261–76.

- Meiller, Larry, Michael Douglass, and Margaret Huettl. “The Complex History of the Marquette and Jolliet Expedition.” The Larry Meiller Show. Wisconsin Public Radio, June 5, 2023.

- Moran, Katherine D. “Making a Founding Father out of a French Jesuit.” In The Imperial Church, 23–53. Cornell University Press, 2020.

- Nelson, Ruth D. Searching for Marquette: A Pilgrimage in Art. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2013.

- Wetterlund, Kris. “American Indians in Tiffany’s Marquette Mural.” Corning Museum of Glass Blog, November 20, 2017.