Laura Sherry and the Wisconsin Players: Little Theatre in the Badger State

[Note: This article was originally published at Acceity.org on 12 May 2011 and was revised and expanded with new sources on 18 June 2012].

The announcement in the New York Times on October 9, 1917, was straightforward and short: “WISCONSIN PLAYERS COMING.” The amateur acting company from Milwaukee, which had been at the vanguard of the American Little Theatre Movement for the better part of a decade, was about to make its East Coast debut.

In bringing the Wisconsin Players to New York, producer Laura Sherry was doing her small part to turn the world of theatre inside out. Before 1910, New York had practically controlled the American stage. A handful of businessmen had held the nation’s theatres in the grasp of their Theatrical Syndicate, which pushed safely profitable productions from New York across the country while locking out competitors.1 Laura Sherry and the Wisconsin Players represented something different: the Little Theatre, an emerging national movement of non-commercial and non-professional drama. It was now time for the actors and writers of the Midwest to bring their ideas to Manhattan.

Laura Case Sherry, whom the New York Times called “the guiding spirit” of the Wisconsin Players,2 had experienced the theatre from both sides — big and little, commercial and amateur. Born in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, in 1876, Laura Case’s parents were Emily Avery and Lawrence Case, owner of the small town’s leading general store. Her parents’ position afforded Laura an education at the University of Wisconsin and the school of speech at Northwestern University. From there she went to study theatre in Chicago and at last New York, where in 1897 she joined the Richard Mansfield Company as an actress and toured the country as a cast member in several plays, including Mansfield’s famous production of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.3 Mansfield, then an opponent of the Theatrical Syndicate, spoke frequently against its stranglehold on the stage, even assailing syndicate bosses inside their own theatres.4 Though Mansfield’s own self-interest later led him to soften his resistance, his early opposition to the centralized commercial theatre must have made an impression on young Laura Case.

At the start of the twentieth century, Case settled back into Wisconsin life. She married Edward P. Sherry, a lumber and paper tycoon from Neenah, and the couple made a home in Milwaukee. There, Mrs. Sherry set to work gathering a club of like-minded theatre devotees and performers.5 The group held meetings and rehearsals in the homes of members, and on April 21, 1909, the amateur troupe staged the one-act Irish drama Riders to the Sea by John Millington Synge at the Davidson Theater in Milwaukee.6 The Irish play was fitting, for the Little Theatre movement in America would draw much of its inspiration from a tour of the United States by the Irish Players in 1911 — but Sherry’s troupe performed Riders to the Sea years before the Irish Players’ visit, demonstrating their foundational role among the nation’s community theaters.7

The nascent Milwaukee association soon gained the support of University of Wisconsin English professor Thomas Dickinson. Unable to produce plays at the university in a time when theatre was not deemed a proper academic subject, Dickinson founded the Wisconsin Dramatic Society in Madison in 1910 and organized a company of players by 1911.8 Dickinson and the Madison group worked closely with Sherry and her Milwaukee compatriots from the start, so that the two associations quickly became branches unified in a statewide society.9 The Wisconsin Players had now been born in earnest.

The Wisconsin Dramatic Society was among the first in a wave of amateur community theatres that cropped up around America in the 1910s. These groups, which also appeared early in cities such as Chicago, Boston, and Detroit, formed a reaction against the melodrama and commercialism that had characterized Broadway under the turn-of-the-century Theatrical Syndicate. Each of the new theatres set its own goals, and many had a particular moral or social objective.10 The aim of the Wisconsin Players was more modest: the society sought to stage plays that had little chance of being shown at Wisconsin’s larger theatres, and to show them at prices anyone could afford. Apart from this interest in making shows more accessible, the society at first admitted no moral or artistic agenda.11

The Wisconsin Players initially pursued their goals by producing a number of foreign and unfamiliar plays, often in translation, and charging only so much for tickets as would cover costs. Dickinson led the group in Madison, while Sherry directed the group’s Milwaukee performances, acting in several of them.12 Apart from these visible roles, Sherry also contributed her organizational talent offstage. She orchestrated readings, fundraisers, and guest lectures, and worked to bring dance and scenic crafts into the society’s purview. Her ultimate vision was to make the group more than an acting company: it was to be an inclusive workshop for theatrical innovation, community participation, and aspiring talent.13

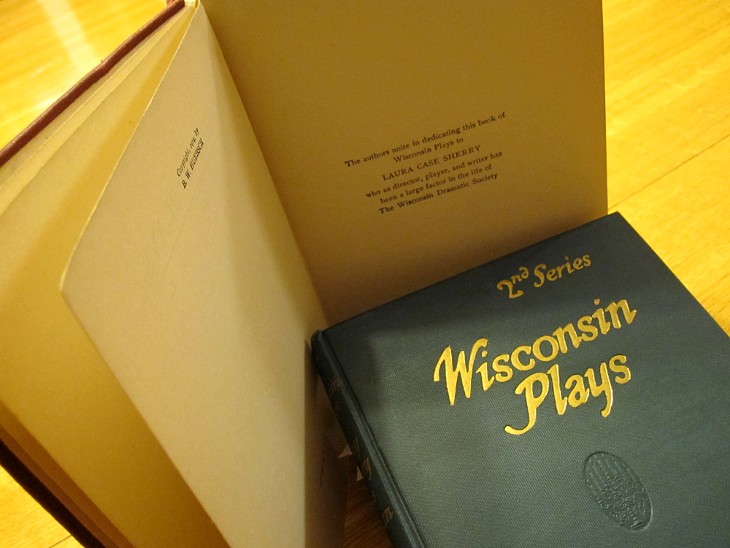

As Sherry and Dickinson encouraged the society to experiment, several members began writing plays for the company to peform. In 1913, under Dickinson’s leadership, the society began publishing a magazine, The Play-book, with original plays and essays on acting, production, scenery, and other elements of stagecraft.14 The following year, the society released the first of two volumes of Wisconsin Plays, a hardbound collection of one-act dramas selected from its repertory.15 These new plays and ideas came from diverse members including men and women, professors and students, trained performers and stage neophytes, and people from both Wisconsin and its neighboring states.

The experimental, member-driven nature of the Wisconsin Dramatic Society gave the group a distinctive artistic style. On stage, the Wisconsin Players sought to develop clarity and realism in their acting, while eliminating distracting flourishes, spotlights, and curtain calls. The society’s plays often featured small casts and short durations, and many of the writers focused on Wisconsin or Midwestern themes in their work.16 One newspaper critic wrote of the society that, “for shockers and thrillers they don’t give a hang, but work more to present life as we generally find it and not its exception.”17

Among its playwrights, the society boasted such talented authors as Zona Gale, William Ellery Leonard, and Howard Mumford Jones. Gale, a native of Portage, Wisconsin, wrote her first play, The Neighbors, for the society in 1914. The play is a comic but warm commentary on neighborliness in the small town setting that Gale knew so well.18 Leonard, a UW English professor alongside Dickinson, looked to local history for his play Glory of the Morning, which presents the dilemma of two métis children in early Wisconsin who must choose between the lifestyle of their Winnebago mother or French father.19 Jones, a student at Madison, explored a more mystical style in The Shadow, a rumination on love’s disappointments set in the clearing of a golden October forest.20

Sherry and Dickinson also tried their hand at experimental play writing. Sherry’s play On the Pier was, in the words of a New York Times reviewer, “a not uninteresting but quite undramatic dialog” with just two characters who meet on a lonely nighttime pier in New York, both uncertain about their future in the big city. The American Review of Reviews called Sherry’s work “a notable piece of modern realistic writing.”21 Dickinson, meanwhile, played with timing, light and silence in his play In Hospital, which centers on a man awaiting the outcome of his wife’s surgery.22

To further the experimental cause of the society, Sherry helped the group acquire a Tudor Revival townhouse in Milwaukee and convert it to a theatrical workshop featuring a tearoom, little theatre, reading room, dance hall, and craft studios. At this spacious headquarters, the players could toy with every aspect of the theatre of their era.23

The Wisconsin Players’ innovations in theatre paralleled the political reforms that made Wisconsin a laboratory of democracy in the early 20th century. It was not that the society’s plays highlighted political subjects — they did not — but the very act of making new theatre of, by, and for the community was a political act. In an article for The Theatre magazine entitled “Dramatic Insurgency in Wisconsin,” author B. Russel Herts compared Sherry, Dickinson, Gale, and Leonard with social reformers La Follette, Ross, Ely and Commons. The Wisconsin Dramatic Society, wrote Herts, aimed “to create a more spiritual culture in the midst of Wisconsin’s economic and social advancement — an intellectual insurgency sprouting from the same soil on which political insurgency has grown.”24 The society proudly accepted the comparison. In its inaugural issue of The Play-book, the society printed an essay by Percy MacKays titled “The Wisconsin Idea in the Theatre.” MacKays argued that the theatre movement was “a necessary and inevitable extension of the Wisconsin Idea,” for through its community workshops and productions, the Wisconsin Dramatic Society aimed to make the same progress for art and spirit that was already being achieved for government and science.25

Zona Gale gave the most eloquent expression to the Wisconsin Players’ democratic ideals: “Whatever one may feel about the ultimate effect of democracy on art, democracy, when it comes, is going to have its art. … The art of democracy will intensify democracy.” The Wisconsin Players, said Gale, did not expect to reform art by promulgating standards for others “to live up, or live down to.” That was “what the Broadway theatres have been doing for years,” and it was autocracy. Instead, the new movement was “opening an area where all who participate in the arts of the theatre may find a laboratory in which to express themselves.” It was “inherently democratic” because it empowered local communities to participate in art and develop new standards of their own.26

By 1917, the Wisconsin Players had a established a wide repertoire of original dramas and built a high reputation across the Midwest. Dickinson had left the society by this time, but it continued to flourish under Laura Sherry.27 Indeed, the players were ready to showcase their ideas in the east. On October 20 that year, the Wisconsin Players made their New York debut at the recently built Neighborhood Playhouse on Grand Street in Lower East Manhattan28 — a venue that, coincidentally, still exists almost unchanged in its exterior appearance. The East Coast premier was a tremendous achievement for the group of Midwestern amateurs.

The New York Times and other papers devoted plenty of attention to Wisconsin group. In an article entitled “Who Is Laura Sherry?”, the Times commended her for invigorating local theatre so that “a community which occasionally boasted of so-and-so who was successful as an artist in Chicago and New York, actually found that they had young people in their own midst who could act, paint, dance, and make music.”29 Critics had both praise and derision for the society’s productions, commenting on the wide difference in talent among the society’s amateurs. The Times gave high marks to Zona Gale’s writing and Laura Sherry’s acting, but questioned the casting and condemned one play by Wallace Stevens as “intended neither for the stage nor the library.”30 The New York Tribune, meanwhile, congratulated the players for “acting sufficiently unprofessional to achieve the illusion of life which the sharp edges of the trained actor are successful in keeping at arm’s length.”31

After the close of their eastern tour, the Wisconsin Players found their schedule interrupted by the American entry to World War I. In 1918, Sherry took a position with the YMCA to direct plays for American troops serving in France. Her commitment to theatre even in a war zone matched her bold assertion that “The theatre is as necessary an institution in our midst as is the hospital — in fact if we had more theaters we would need fewer hospitals. The human mind, in order to be a normal healthy one, requires a certain amount of relaxation — it must be taught to play as well as how to work.”32 This perspective was a clear change from the puritanical sentiment that had not much earlier regarded the stage as a degrading and immoral influence on the spirit.

In Europe until late 1919, Sherry toured the battlefields of the Western Front and, at one point, composed a letter to her husband in Milwaukee across the backs of one hundred French postcards. During her time abroad she developed a fascination with Europe that prompted several return trips, including one voyage to Russia to meet famed director Constantin Stanislavski.33

There were no more major tours for the Wisconsin Players following the war, but the group remained active in Milwaukee. Laura Sherry continued to work with the players into the 1930s.34 Many of the early members of the society went on to further success during this time. In 1921, Zona Gale became the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for her play Miss Lulu Bett.35 W.E. Leonard achieved wide recognition for his translation of Beowulf to Modern English in 1923,36 and Howard Mumford Jones joined the faculty at Harvard where he would garner his own Pulitzer Prize much later in life for scholarly work.37 Sherry also followed new interests, most notably publishing a volume of poetry in Paris in 1931 entitled Old Prairie du Chien, which drew on the French-Canadian culture of her childhood home.38

Laura Case Sherry passed away in 1947 at the age of 71. Notice of her death appeared in the New York Times and Billboard magazine.39 The Little Theatre was no longer an insurgent movement, for it had inspired an outgrowth of community theatres across America and set the scene for the Off-Broadway movement of the mid-Twentieth Century. Just as importantly, Sherry and the Wisconsin Players had given dramatic expression to the culture of their native state, bestowing an artistic legacy for all Wisconsinites. Today, as we go in search of experiences for our own lives richer than those afforded by TV and computer screens, we would do well to remember how Sherry and the Wisconsin Players made theatre out of the men, women, and materials in their midst. We retain the same creative potential in ourselves. “The sheer ecstasy of emerging from one’s everyday self into an imaginary creature of another world or plane,” Laura Sherry once remarked, “is invaluable.”40

Notes and References:

- Walter Prichard Eaton, “The Theatre: The Rise and Fall of the Theatrical Syndicate,” American Magazine, vol.70 no.6 (October 1910), p.832; and Don B. Wilmeth, ed, The Cambridge Guide to American Theatre, 2nd ed., (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), p.634.

- “Who Is Laura Sherry?” New York Times, 28 October 1917.

- Mrs. William H.L. Smythe, “Laura Case Sherry” in Famous Wisconsin Women vol.2 (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin Women’s Auxiliary, 1972).

- Paul Wilstach, Richard Mansfield: the Man and The Actor, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908), pp.288-289.

- Richard Boudreau, “Wisconsin woman sparked Little Theater: Woman was pioneer in town dramatics,” St. Paul Sunday Pioneer Press, 12 September 1976, Wisconsin edition.

- Edward P. Halline, “Wisconsin Players Pioneered in Little Theater Movement: Organization Going Strong After 30 Years; Mrs. Sherry One of Founders,” Milwaukee Sentinel, 12 November 1939.

- The Cambridge Guide to American Theatre lists the 1911 visit of the Irish Players first among the events and conditions leading to the flowering of the Little Theatre movement (Wilmeth, p.178). The New York Times made note of the fact that the Wisconsin Players had performed Riders to the Sea in Milwaukee before the Irish Players toured America (“Who Is Laura Sherry?” 28 October 1917). See also Halline for the influence of the Irish Players in Wisconsin.

- Robert E. Gard, Grassroots Theater: A Search for Regional Arts in America (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1999), pp.85-86; and Thomas H. Dickinson, “The Insurgent Theatre,” (New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1917), pp.70-71.

- “Who Is Laura Sherry?”; Gard, p 87; and Halline.

- Constance D’Arcy MacKay, The Little Theatre in the United States, (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1917).

- “Gives Stage Aims: Wisconsin Dramatic Society Explains Its Motives,” Milwaukee Journal, 28 November 1911. William Ellery Leonard, “The Wisconsin Dramatic Society: An Appreciation,” The Drama: A Quarterly Review of Dramatic Literature vol.2 no.6 (May 1912), pp.222-237.

- William Ellery Leonard, “The Wisconsin Dramatic Society: An Appreciation,” The Drama: A Quarterly Review of Dramatic Literature vol.2 no.6 (May 1912), pp.222-237.

- John Collier, “The Stage, a New World,” The Survey, vol.36 no.10 (3 June 1916), p.256; and Smythe.

- Wisconsin Dramatic Society, The Play-book vol.1 no.1, (April 1913); and “Drama in Wisconsin: An Unusual Product of the Middle West,” Boston Evening Transcript, 4 April 1913.

- Thomas H Dickinson, ed., Wisconsin Plays, (New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1914).

- Leonard, pp.229-230,232-233; and MacKay, pp.144-145.

- “Woman’s Clubs: Players Win Praise,” Milwaukee Journal, 17 November 1916.

- Zona Gale, “The Neighbors,” Wisconsin Plays, ed. Thomas H. Dickinson, (New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1914), pp.1-68; and “Miss Gale of Portage,” New York Times, 2 January 1921.

- William Ellery Leonard, “Glory of the Morning,” Wisconsin Plays ed. Thomas H. Dickinson, (New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1914), pp.113-187; and “Wisconsin Drama: As Old-Fashioned as Many of Its Vaunted Social ‘Reforms’,” New York Times, 14 April 1912.

- Howard Mumford Jones, “The Shadow,” Wisconsin Plays: Second Series, (New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1918), pp.83-136.

- Laura Sherry, “On the Pier,” Wisconsin Plays: Second Series, (New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1918), pp.53-82; “‘Wisconsin Players’ Here,” New York Times, October 22, 1917; and “The New Books: Plays and Playwrights,” The American Review of Reviews vol.58 no.3 (September 1918), p.332.

- Thomas H. Dickinson, “In Hospital,” Wisconsin Plays ed. Thomas H. Dickinson, (New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1914), pp.69-112.

- Zona Gale, “The Wisconsin Players,” Theatre Arts Magazine, vol.1 no.3 (May 1917), pp.128-130; and Collier, p.256.

- B. Russel Herts, “Dramatic Insurgency in Wisconsin,” The Theatre vol.17 no.143 (January 1913), p.27.

- Percy MacKays, “The Wisconsin Idea in the Theatre,” The Play-book, vol.1 no.1 (April 1913).

- Zona Gale, “The Wisconsin Players.”

- “Who is Laura Sherry?”; and Halline.

- “Wisconsin Players Coming,” New York Times, 9 October 1917; and “‘Wisconsin Players’ Here.”

- “Who is Laura Sherry?”

- “‘Wisconsin Players’ Here.”

- New York Tribune quoted in Zona Gale, “Introduction,” Wisconsin Plays: Second Series, (New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1918).

- Smythe; Boudreau.

- “100 Post Cards Tell Her Story,” Milwaukee Sentinel, 18 June 1919; Smythe; and Boudreau.

- Halline.

- “Zona Gale,” Topics in Wisconsin History, Wisconsin Historical Society, http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/topics/gale/ (accessed 12 May 2011).

- “Leonard, William Ellery,” Dictionary of Wisconsin History, Wisconsin Historical Society, http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/dictionary/index.asp?action=view&term_id=2571&search_term=leonard, (accessed 12 May 2011).

- “A Remembrance of Howard Mumford Jones,” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences vol.34 no.2 (November 1980), pp2-4.

- Laura Sherry, Old Prairie du Chien, (Paris: Edward W. Titus, 1931).

- “Laura Sherry Dies in East,” Milwaukee Journal, 18 April 1947; “Mrs. Edward P. Sherry,” New York Times, 19 April 1947; and “The Final Curtain”,” Billboard vol.59 no.17 (3 May 1947), p.46.

- Sherry, quoted in Smythe.