Floods Strike Again: A Case For Land Conservation

The Summer of 2013 began with floods, washouts, and landslides across the Driftless Area, destroying roadways and inundating homes in Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota. These events bring significant losses and make dramatic news, but they are not new. To the contrary, the Driftless Area’s rugged landscape owes its very existence to millions of years of erosion by floodwater, and that erosion is an ongoing process. Widespread human construction, by contrast, is a recent development in this environment. The repeated rains and landslides of the last decade make clear that communities in the Driftless Area must plan their land use for the inevitable occurrence of further flooding and erosion.

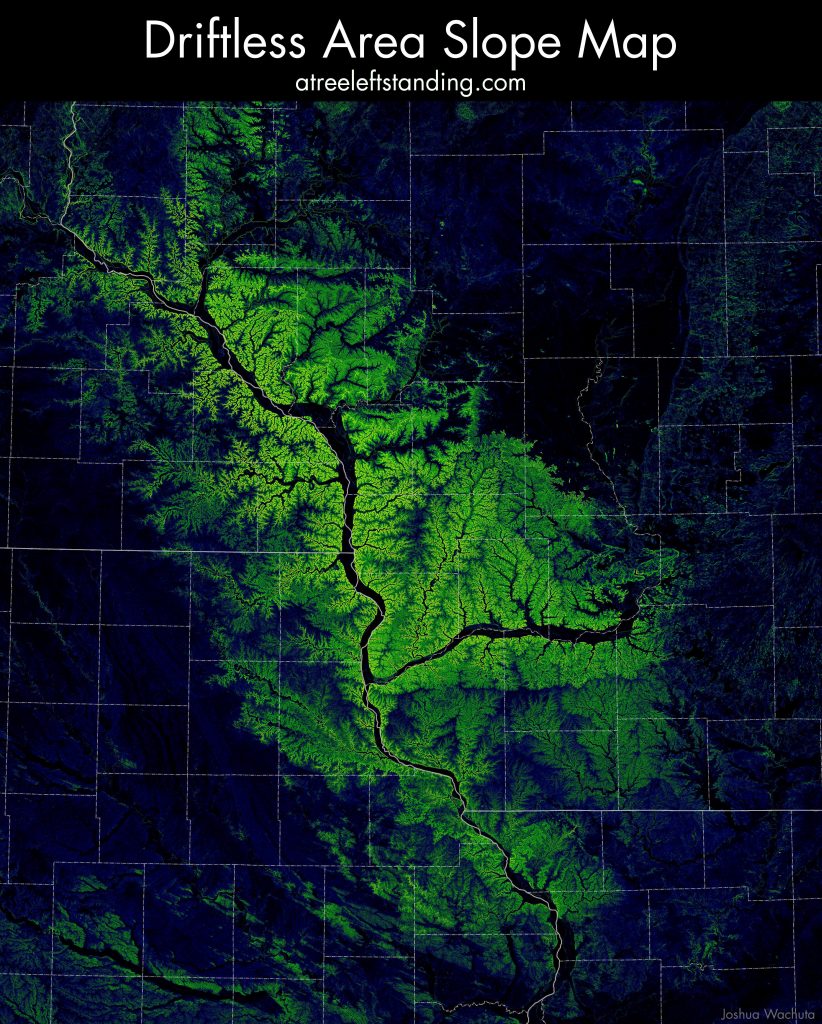

The Driftless Area is prone to flash-floods and landslides in part because of its unique topography, which has a higher degree of slope than surrounding regions. The following map (view map at high-resolution) is colored by slope to highlight this distinction, with steeper hillsides shaded more brightly than level land. The Driftless Area stands out immediately as the bright swath across the center of the map:

The steep terrain of the Driftless Area increases the speed at which run-off collects into drainage channels, ordinarily an advantage, as it dries uplands quickly and prevents water from pooling into stagnant ponds and bogs. During heavy rains, however, water collects more rapidly than some narrow channels can accommodate, leading to sudden flash floods that erode banks and scour new channels. In the meantime, the saturated hillsides — especially those with inadequate vegetation — lose strength and give way, leading to landslides. These are the very processes that created the jagged valleys and steep slopes of the Driftless Area, a landscape forged in unison with running water.

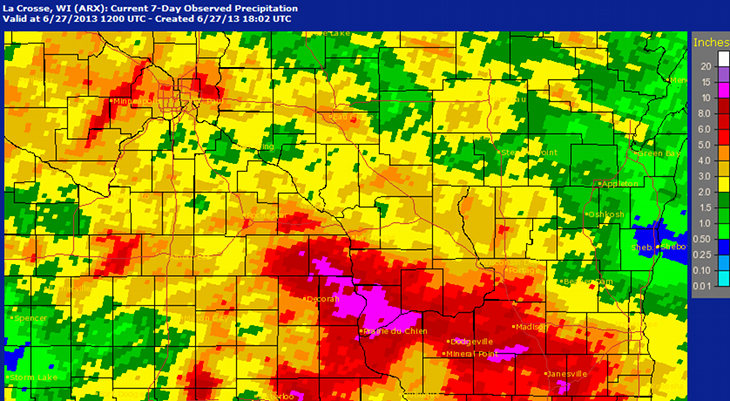

Today only very heavy rains overwhelm the Driftless Area’s timeworn valleys, and between ten and thirteen inches of rain fell between Prairie du Chien and Boscobel, Wisconsin, during the week from June 20 to June 27, 2013. The National Weather Service at La Crosse, Wisconsin, mapped the rainfall totals across the region:

Although the storms of June 2013 seem extraordinary, a cursory look at the past decade reveals that rains on this magnitude are not unusual. Between June 6 and June 13, 2008, as much as eleven inches of rain fell in northern Vernon County, Wisconsin, sending the Kickapoo River to record crests in downriver villages including Soldiers Grove and Gays Mills. On the weekend of August 18-19, 2007, storms dumped seventeen inches of rain at Witoka, Minnesota, and over twelve inches at Stoddard, Wisconsin, where homes and roads alike tumbled downhill on a torrent of mud and debris. Another storm on May 8, 2004, unloaded five inches of rain between De Soto, Wisconsin, and Lansing, Iowa, sending mud over roads and backyards. In the present climate, overwhelming rains appear to visit the Driftless Area roughly every two to three years, making future floods virtually certain.

Local farmers and residents recognized long ago, through trial and error, that human development in the Driftless Area must plan for the inevitability of floods and erosion. European newcomers to the region in the nineteenth century had platted towns in floodplains and plowed fields that destabilized hillsides. By the early twentieth century, their mistakes were clear: huge quantities of fertile topsoil from ridge-top fields had washed into the valleys, plugging-up and banking-in streams and exacerbating flash floods. The New Deal began to mitigate soil erosion in the 1930s by promoting new agricultural methods. Contour strip farming, piloted near Coon Valley, saw farmers begin to plow crop rows parallel to the curving hillsides rather than straight up and down slopes, slowing the flow of run-off. Later, low-lying settlements including Prairie du Chien, Soldiers Grove, and more recently Gays Mills, made the tough decision to relocate whole neighborhoods away from flood-prone areas rather than continuing futile battles against climate and geography. These actions put human land use in the Driftless Area on a more sustainable footing, but sustainability requires ongoing effort.

The Driftless Area faces environmental strain today not only from agriculture, but also from hillside clearance due to the growth of frac sand mining and the spread of rural subdivisions and recreational developments like trails and campgrounds. These activities provide economic benefits to the region, and none of them is inherently wrong, but all such land uses must be planned with clear acknowledgement of their impact on run-off and soil erosion. The Driftless Area’s rugged hillsides may seem like scenic sites for homes or campgrounds, but these abrupt slopes were formed by an ongoing process of erosion by running water. Rather than denying this reality — not to mention despoiling the local scenery — steep slopes are best conserved in their natural state. Similarly, roads and driveways must be built for high water at stream crossings and strive not to constrict natural drainage channels and worsen flash floods. Although a powerful political movement has lately campaigned to roll back regulations and cut funds for the agencies that enforce them, the proper regulation of land use is in fact essential to defending property rights in an environment where poor soil management by one land owner can erode away a neighbor’s hillside or bury a downstream town in mud.

Storms and floods are inevitable in the Driftless Area, but human land use has the potential to soften or worsen their impact. Environmentally-aware planning will save both lives and property by keeping human construction out of the way of flash floods and landslides. Local communities must continue to evaluate the consequences of their development and push forward their tradition of working towards greater harmony with the land. If they do, they can ensure a more secure future for both the landscape and its residents.

No Responses to "Floods Strike Again: A Case For Land Conservation":

Continued abuse of farmland through years of row cropping combined with continued tiling of wetlands and the amazing rate that our once prevalent prairie terrain disappears into more cropland spells doom beyond the ethanol or frac sand booms of the last twenty years. It’s not about the fishermen making a stand, it’s a stand a different way of how we think, do business, and treat the land that will ultimately seal the fate of the area. We are headed to more of a bottoming out than anything we have ever seen. Things wil get much worse before they improve.