Jack-in-the-Pulpit

a blog by Joshua Wachuta

After more than a decade under the title “Acceity,” I have renamed this site “A Tree Left Standing.” It’s a bit longer and a bit less whimsical. But I hope it is more pronounceable, more meaningful, and easier to remember and spell.

The address has changed to atreeleftstanding.com, but old links should continue to work for some time thanks to the magic of HTTP redirection.

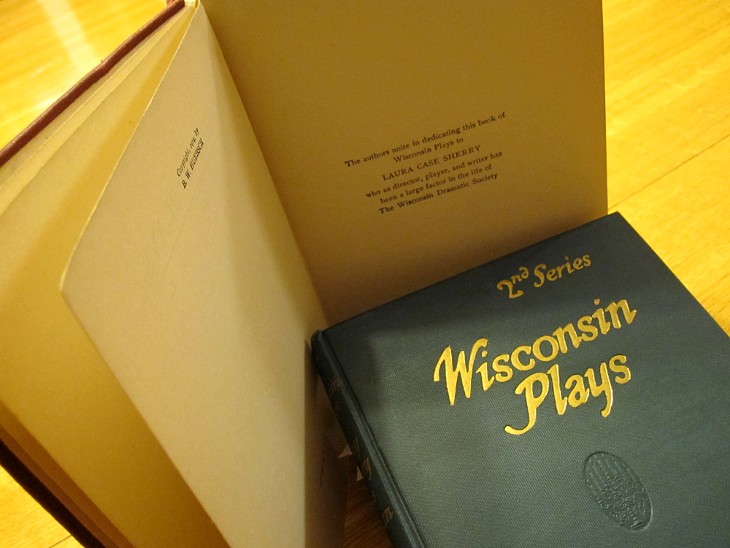

The new title, A Tree Left Standing, stands for preserving memories, learning from the past, and conserving the planet that we all share. It comes from the poem “An Old Settler” by Laura Case Sherry. The poem is not my favorite — Sherry wrote many better ones — but the opening lines work well as a metaphor for this blog.

Continue reading →A tree left standing

Laura Case Sherry, “An Old Settler”

From a grove that has been cut away…

The Summer of 2013 began with floods, washouts, and landslides across the Driftless Area, destroying roadways and inundating homes in Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota. These events bring significant losses and make dramatic news, but they are not new. To the contrary, the Driftless Area’s rugged landscape owes its very existence to millions of years of erosion by floodwater, and that erosion is an ongoing process. Widespread human construction, by contrast, is a recent development in this environment. The repeated rains and landslides of the last decade make clear that communities in the Driftless Area must plan their land use for the inevitable occurrence of further flooding and erosion.

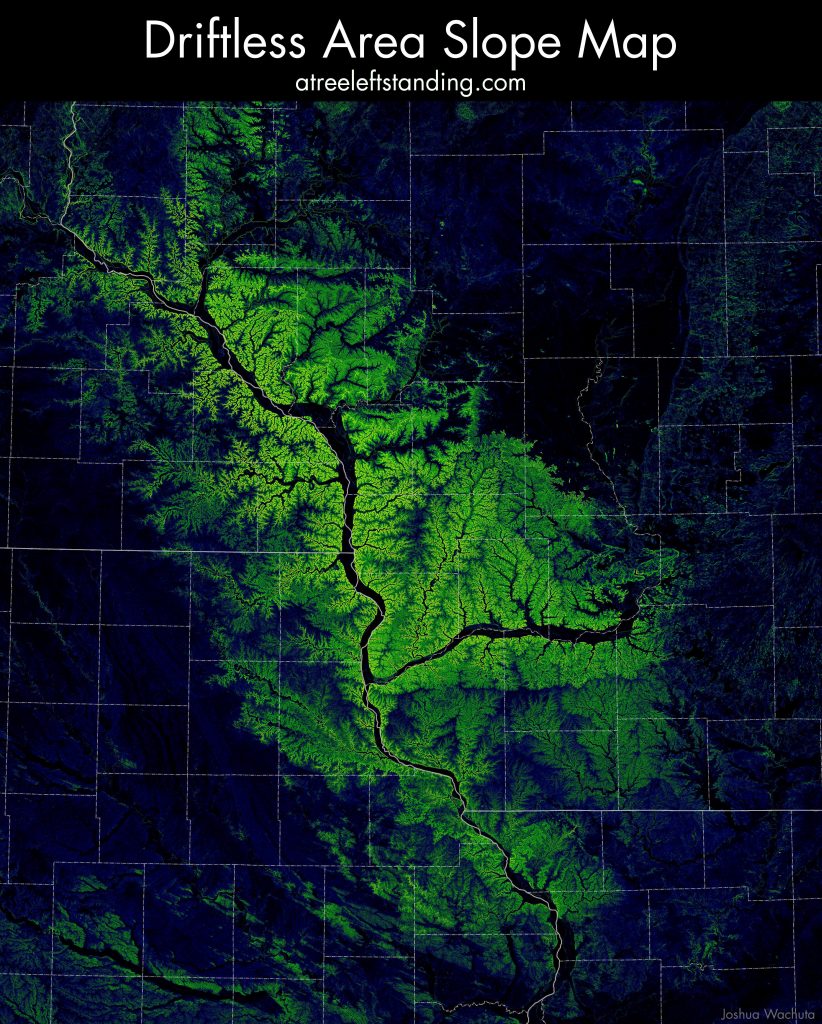

The Driftless Area is prone to flash-floods and landslides in part because of its unique topography, which has a higher degree of slope than surrounding regions. The following map (view map at high-resolution) is colored by slope to highlight this distinction, with steeper hillsides shaded more brightly than level land. The Driftless Area stands out immediately as the bright swath across the center of the map:

The steep terrain of the Driftless Area increases the speed at which run-off collects into drainage channels, ordinarily an advantage, as it dries uplands quickly and prevents water from pooling into stagnant ponds and bogs. During heavy rains, however, water collects more rapidly than some narrow channels can accommodate, leading to sudden flash floods that erode banks and scour new channels. In the meantime, the saturated hillsides — especially those with inadequate vegetation — lose strength and give way, leading to landslides. These are the very processes that created the jagged valleys and steep slopes of the Driftless Area, a landscape forged in unison with running water.

Upon a New Year’s Eve some centuries ago, on an ice-locked island in Lake Michigan, a motley troupe of old fishermen donned grotesque costumes and trudged into the snow. As they ambled about their moonlit village, they rapped on the door of each cabin, presenting a frightening sight to the families within at their firesides, and singing each household a medieval chanson:

Bon jour, le Maître et la Maîtresse,

Et tout le monde du loger.

Si vous voulez nous rien donner, dites-le nous;

Nous vous demandons seulement la fille aînée.

This was the French custom of La Guignolée — New Year’s Eve begging — and all that the singers sought, if a host could give no more, was the eldest daughter of the house: la fille aînée. Each home was ready with other gifts, however — for the chanteurs were always expected that night and fêted in exchange for their entertaining song and dance.1 Thus the elderly Mackinac Island fishermen preserved a dying tradition of their medieval French forbears, and the nineteenth century settlers of America’s Old Northwest ushered in another New Year.

All New Year’s customs seem a smidgen strange. For the sake of no more than a new calendar, even in our modern age, we drop everything — crystal balls, shoes, peaches, carp, you name it — to celebrate with champagne and Scottish song. These observances often seem like nothing but the scrag end of Christmas, one last tenuous excuse for revelry before packing up and buttoning down for winter. In the Old Northwest, however, New Year’s was among the most anticipated and most fondly recalled of all the holidays — more so even than Christmas.

⬑ I. The River: I’ve lately flown into the city…

⬑ II. The Rails: …a landscape where timelines entwine…

⬑ III. The Road: …forever rolling, shifting, changing…

⬑ IV. The Lake: …like sand below the waves.

In 1962, the U.S. Congress authorized construction of a flood control dam on the Kickapoo River at La Farge, Wisconsin. The dam would protect La Farge and its downstream neighbors from the Kickapoo’s devastating flash floods. It would also create a 1,780 acre reservoir — “Lake La Farge” — that proponents hoped would draw tourists in search of fishing, boating, and lakefront recreation. Over a hundred farmers and landowners were made to sell their real estate to the federal government beginning in 1969 to make way for the planned reservoir. Construction crews set to work rebuilding Wisconsin Highway 131 around the anticipated lake. In 1971, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers broke ground on an earthen dam at La Farge.

As work progressed, increased environmental scrutiny revealed problems. Studies showed that a dam would not only alter the local ecology and threaten endangered species in the Kickapoo Valley, but also take a severe toll on local water quality. The expense of maintaining the reservoir also raised concerns. In 1975, with the dam partially in place and half of the affected highway rebuilt, a failed cost-benefit analysis led the Corps of Engineers to halt the project. The cost had been $18 million, coupled with the destruction of the valley’s farming community — an unambiguous example of poor foresight and government waste.

Though Lake La Farge was never filled, the incomplete dam and an abrupt corner in Highway 131 remain as visible reminders of the failed project. Likewise, the property acquired for the reservior remains largely vacant, though it at last found use in 2000 when it was transferred from the Corps of Engineers to the Ho-Chunk Nation and the State of Wisconsin for the creation of the Kickapoo Valley Reserve. The lake that never was thus remains fixed on the mental map of many Kickapoo Valley residents.

I created the map above to define the extent of the planned lake more clearly. The map is based on elevation data I had downloaded from the USGS NED for my Driftless Area Map, and it simulates the area that would have been flooded if Lake La Farge had been filled to the proposed elevation of 840 feet above sea level. The base layer of the map is a mosaic of 2010 aerial imagery from the USDA National Agricultural Imagery Program. The map does not account for sediment deposition and other landscape changes that the dam could have wrought, but it offers a general picture of how “Lake La Farge” might have fit into the modern landscape.

Brad’s History – From Brad Steinmetz, author of That Dam History: The Story of the La Farge Dam Project.

The Kickapoo Valley Reserve – the valley today, with several pages of history

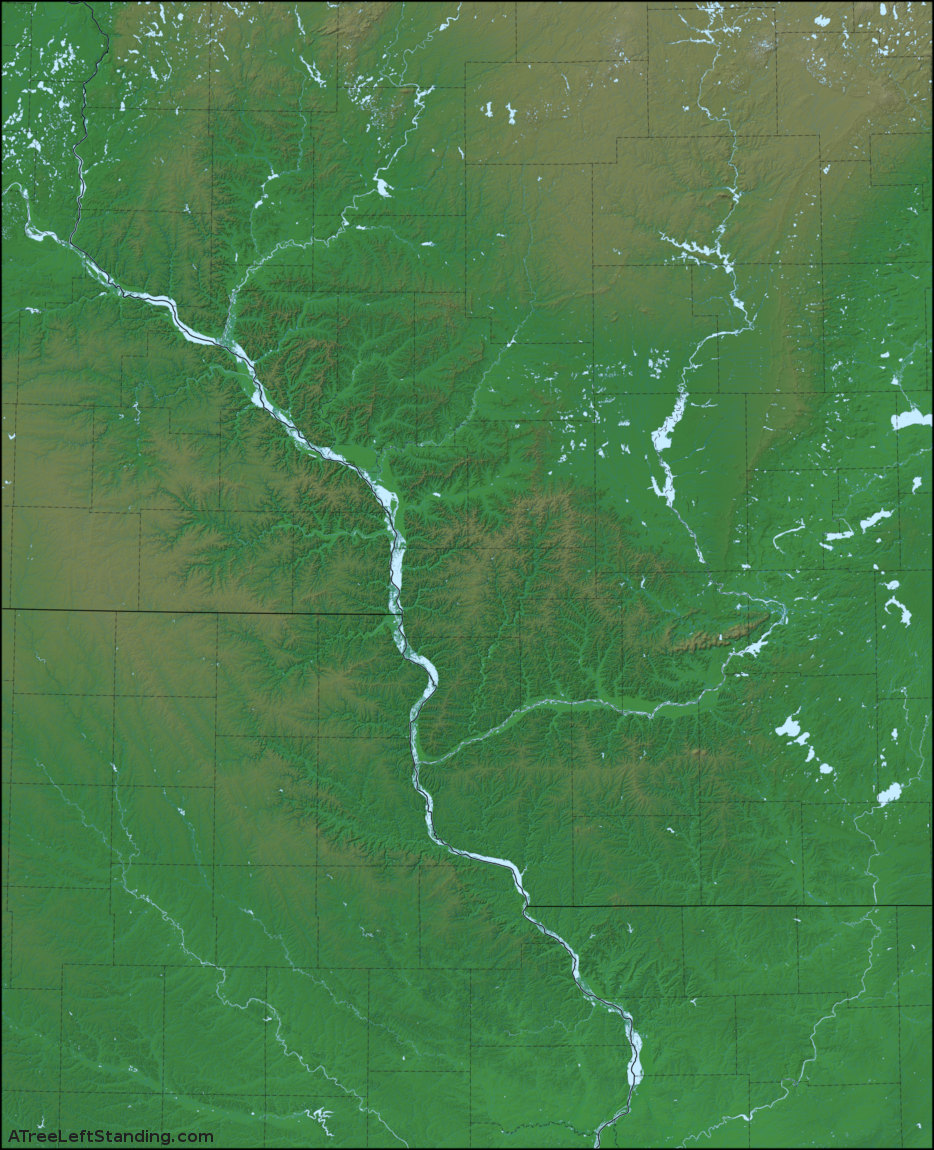

My home is the Driftless Area — a landscape of rugged hills and coulees that unfolds in steep contrast to the plains of the surrounding Midwest. I’ve long wanted a good map of the area’s unique topography, but this desire has been hard to satisfy. The Driftless Area is flung across the borders of Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, so no individual state map covers the whole region. Moreover, while there are a handful of maps out there centered on the Driftless Area, none that I’ve seen show quite what I want. There was just one solution: I would have to make a map of my own. I have no formal training in GIS or cartography, but maps have fascinated me since childhood, and there is no better excuse than ignorance for learning something new. It took some time, but at long last I’ve made the map I’d been looking for.

The Driftless Area takes its name because it is comparatively free of glacial “drift,” the silt and stone carried elsewhere by ice age glaciers. Though prehistoric ice sheets passed the Driftless Area on all sides, this region mostly escaped the scouring glaciation that flattened the neighboring countryside. As a result, the Driftless Area exhibits a more timeworn terrain, visible on the preceding map as a swath of rough relief stretching from northwest to southeast. For all its hills, the area is not mountainous — its highest elevation, at West Blue Mound in Wisconsin, is only 1,719 feet above sea level. In fact, the Driftless Area was built up from sediment in a shallow Paleozoic seabed. Ever since the region rose out of the sea hundreds of millions of years ago, streams have been eroding deep, fractal-like drainage channels into the land, creating its present rough surface.1

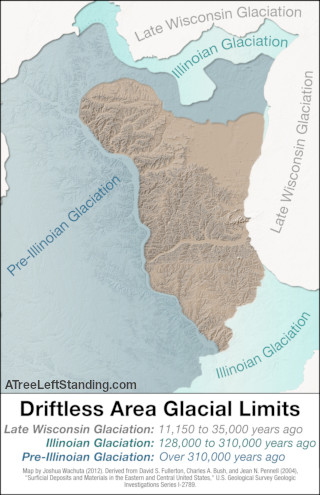

During the last 2.5 million years, ice sheets repeatedly advanced and retreated around the Driftless Area. The accompanying map shows the estimated limits of these glacial advances. The most recent glacial maximum, called the Late Wisconsin, can be mapped with great accuracy. In the Late Wisconsin period, ice sheets spanned from Canada to southern Ohio, leaving behind the lakes, drumlins, and moraines that characterize the geography of eastern and northern Wisconsin. Glaciers in this period did not penetrate the Driftless Area, however. Earlier glacial periods are more difficult to map with precision, but it seems clear that the Illinoian Glaciation also passed around the Driftless Area. On the other hand, geologists have unearthed scattered Pre-Illinoian glacial deposits in the western and far northern portions of the Driftless Area. By definition, Pre-Illinoian glaciation took place at least 310,000 years ago. The ice that once encroached into the Driftless Area probably came even earlier — the magnetic polarity of the region’s glacial deposits indicate that they were formed more than 790,000 years before present. As a result, evidence of that early glaciation has had time to mostly erode away.2

The erosion of the Driftless Area was exacerbated by cataclysmic floods that followed each glacial period. During the last glacial phase, meltwater pooled along the northeast periphery of the region, where a combination of ice and hills held back Glacial Lake Wisconsin. The lake created a broad, sandy bed that remains visible today as flat expanse of lowlands across the central part of the state. When this prehistoric lake overcame its constraints, it unleashed floods that eroded the present valleys of the Black River and the Lower Wisconsin River. Similar outpourings of glacial meltwater molded the Chippewa River and Mississippi River valleys. The last retreat of glaciers from Wisconsin between 14,000 and 10,000 years ago established these rivers in their present courses, leaving the Driftless Area essentially in its modern form just as the first humans made their way into the landscape.3

I wanted my map of the Driftless Area to reveal at a glance the shape of the natural landscape. Human development and labels were less important, as I can find road maps from Yahoo! and Google, and in any case, the cultural features of the Driftless Area tend to rise from their natural surroundings. River valleys such as the Mississippi and Wisconsin doubled as arteries of trade and transportation. Alluvial terraces became building sites for towns and cities like Winona, La Crosse, and Prairie du Chien. Stretches of highland like Military Ridge became thoroughfares linking upland settlements, and prominent features like the Blue Mounds and Trempealeau mountain have long served as landmarks for passersby. A map that makes these natural features visible will therefore expose the foundations of human geography in the region.

After deciding on an emphasis for my map, I needed to collect the geospatial data and software needed to make it. I was able to complete the map with public domain data from U.S. government agencies. To process this data, I relied exclusively on free open source software. GRASS (with GDAL and OCR) did the heavy work of rendering my data sources into graphical map layers, while Inkscape and GIMP aided me with further graphic editing and layer compositing — all on a GNU/Linux operating system.

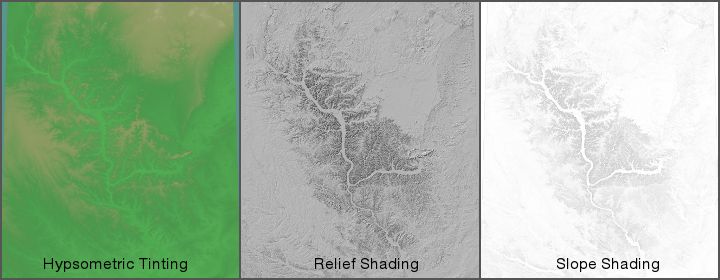

Land elevation formed the basis for my map. I downloaded local elevation data from the National Elevation Dataset (NED) maintained by the United States Geological Survey. The NED is a raster or grid of elevation measurements spaced at every 1 arc second (1/360th of a degree, or approximately 30 meters) across the entire contiguous United States (other levels of detail, such as measurements at every 1/3 arc second, are also available). I used GRASS to map these elevation measurements in three ways. First, I defined a different color to mark each elevation level — rising from green lowlands to brown uplands. This is a cartographic technique known as “hypsometric tinting,” and it serves to fill the map with color while making it easy to compare the height of distant locations at a glance. Second, I instructed GRASS to draw simulated shadows behind rises of elevation, creating a classic “shaded relief” map. This provides a three-dimensional illusion of the rise and fall of terrain. Finally, in addition to traditional relief shading, I also utilized GRASS to draw subtle “slope shading,” making steeper areas appear slightly darker than flat areas. This outlines hillsides even at angles that standard shaded relief would miss.

As I created these three elevation layers, I also needed GRASS to project my renderings onto a plain — the earth is round, but maps are flat. There is no perfect way to depict the spherical surface of our planet in two dimensions, and as a result cartographers have designed countless map projections that compromise shape or scale in different ways to make the best approximations for different needs. I used the transverse Mercator projection for my map of the Driftless Area, as that projection is ideal for mapping small regions that are longest from north to south. Below are samples of my three elevation renderings — hypsometric tinting, shaded relief, and slope shading — each as a transverse Mercator projection:

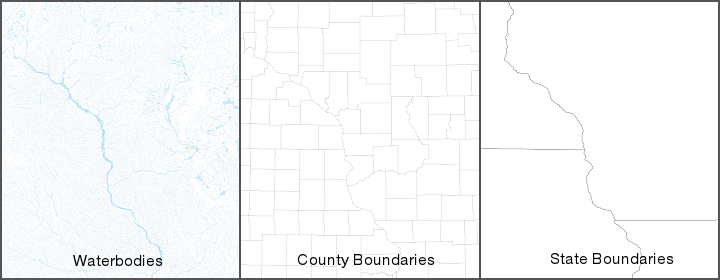

After mapping elevation, I added a few more elements. Streams are responsible for the erosion that created the Driftless Area’s topography, so I wanted to show water features in as much detail as possible. I was able to obtain outlines of streams and waterbodies from the USGS National Hydrography Dataset and the U.S. Census Bureau’s TIGER mapping service. I also downloaded state and county boundary definitions from the Census Bureau. Although I left out other human features on my map, I included boundaries to serve as a location reference and enable easy comparisons with maps that emphasize man-made features. As before, I rendered both the water features and boundaries as a transverse Mercator projection using GRASS. I then turned to Inkscape to color and pattern each set of features, creating the maps below:

When I had at last prepared each layer of the final map — state and county boundaries, water bodies, and three renderings of elevation — I used GIMP to stack the layers together. The resulting composite map was shown at the start of this article.

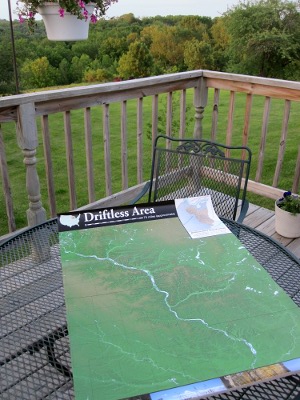

I still was not done. It was not enough merely to pan across the map on my computer screen — the only way to study the whole region in detail would be to order a large format print of the map. A print would need to be as polished and informative as possible, so I went back to the USGS for more data and used GRASS and GIMP to create a map of local glaciation (included in part one of the article) as well as a locator map based on the contiguous United States. I inset these additions onto the main map for added reference value in the final printed version. Finally, I embellished the map with photographs showing four seasons of Driftless Area natural scenery. I sent the design away to be printed, and in a few days, I had the map in my hands as a 24 by 36 inch poster.

This map was made to be shared. You can get the 24 by 36 inch print for yourself by ordering the Driftless Area Map Poster from Zazzle. I wouldn’t hawk the poster if it wasn’t absolutely the best way to see the map in all its detail. A portion of your purchase also helps keep this website alive and free of outside advertising.

Get the Driftless Area Map Poster (24 by 36″)

Not ready to buy the poster? No worries! I’m also giving the map away as a 1280-pixel JPG for screen viewing. It’s not quite the same as having the print for your wall, but it is free. Just right click on

Download the Driftless Area Map and select the “Save” option from your browser’s context menu.

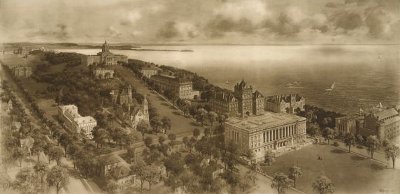

This September marks the beginning of fall term for more than 180,000 students across the twenty-six campuses of the University of Wisconsin System. The return to school is an opportunity for reunion and renewal, for the discovery of new possibilities and the re-evaluation of old ideas — including the idea of public higher education itself. If this idea is to remain relevant in the years to come, then we must value public universities as something more than a monetary cost to taxpayers and a dollar discount to tuition payers. At the foundation of any real public state university there is a deeper value: service and accountability to the people who make up the state. One need not look farther than the development of the University of Wisconsin itself for an illustration of what this ideal means.

The University of Wisconsin and the State of Wisconsin were created in the same stroke. Article 10, Section 6 of the Wisconsin Constitution of 1848 declared:

“Provision shall be made by law for the establishment of a state university, at or near the seat of government, and for connecting with the same, from time to time, such colleges in different parts of the state, as the interests of education may require.”

Wisconsin’s founders called for a public university in the state constitution, and established the seat of learning as one with the seat of law, because they had an ideal of cultivating productive citizens, and educated citizens, and cultured citizens, but above all else, citizens — participants in a democracy and shapers of law, not mere subjects either of crown or wealth. John Lathrop, the first UW Chancellor, expressed this concept eloquently at his inaugural address on January 16, 1850:

“The American mind has grasped the idea, and will not let it go, that the whole property of the state, whether in common or in severalty, is holden subject to the sacred trust of providing for the education of every child of the state. Without the adoption of this system, as the most potent compensation of the aristocratic tendencies of hereditary wealth, the boasted political equality of which we dream is but a pleasing illusion. Knowledge is the great leveler. It is the true democracy. It levels up—it does not level down.”1

As it grew, the University of Wisconsin only strengthened in its commitment to knowledge as true democracy. In 1894, when economics professor Richard T. Ely was attacked by in the national press as an anarchist and socialist radical for his research interest in the growing labor movement, the UW Board of Regents convened hearings to investigate, and concluded them by issuing a famous defense of the professor and the freedom to pursue knowledge:

“We cannot for a moment believe that knowledge has reached its final goal, or that the present condition of society is perfect. We must therefore welcome from our teachers such discussions as shall suggest the means and prepare the way by which knowledge may be extended, present evils be removed and others prevented. We feel that we would be unworthy of the position we hold if we did not believe in progress in all departments of knowledge. In all lines of academic investigation it is of the utmost importance that the investigator should be absolutely free to follow the indications of truth wherever they may lead. Whatever may be the limitations which trammel inquiry elsewhere we believe the great state University of Wisconsin should ever encourage that continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found.”2

Some twenty years after the regents made this proclamation, their “sifting and winnowing” statement was affixed in bronze to University Hall (since renamed for UW President John Bascom), becoming an enduring reminder of the commitment to truth.

In the meantime, the University of Wisconsin had begun to redefine the ways in which knowledge could be disseminated and truth be put to the service of democracy. Under the leadership of Charles Richard Van Hise, UW President from 1903 to 1918, the university advocated what became known around the United States as the Wisconsin Idea: a notion often summarized in the slogan “the boundaries of the campus are the boundaries of the state,” meaning that the role of the public university should be public service to all the people of the state and their government — not only the researchers and students on campus. Theodore Roosevelt remarked on this ideal that:

“In no other State in the Union has any university done the same work for the community that has been done in Wisconsin by the University of Wisconsin. … I found the President and the teaching body of the University accepting as a matter of course the view that their duties were imperfectly performed unless they were performed with an eye to the direct benefit of the people of the State; and I found the leaders of political life, so far from adopting the cheap and foolish cynicism of attitude taken by too many politicians toward men of academic training, turning, equally as a matter of course, toward the faculty of the University for the most practical and efficient aid in helping them realize their schemes for social and civic betterment.”3

The “work for the community” that Roosevelt observed one hundred years ago had a wide scope. Sure, the University of Wisconsin at the dawn of the 20th century offered tuition-free admission to Wisconsin residents, paid for by state taxpayers and federal grants — but this was only typical for a public university of the period. What set Wisconsin apart were the university’s efforts to reach beyond traditional student instruction to improve life across the state.

[Note: This article was originally published at Acceity.org on 12 May 2011 and was revised and expanded with new sources on 18 June 2012].

The announcement in the New York Times on October 9, 1917, was straightforward and short: “WISCONSIN PLAYERS COMING.” The amateur acting company from Milwaukee, which had been at the vanguard of the American Little Theatre Movement for the better part of a decade, was about to make its East Coast debut.

In bringing the Wisconsin Players to New York, producer Laura Sherry was doing her small part to turn the world of theatre inside out. Before 1910, New York had practically controlled the American stage. A handful of businessmen had held the nation’s theatres in the grasp of their Theatrical Syndicate, which pushed safely profitable productions from New York across the country while locking out competitors.1 Laura Sherry and the Wisconsin Players represented something different: the Little Theatre, an emerging national movement of non-commercial and non-professional drama. It was now time for the actors and writers of the Midwest to bring their ideas to Manhattan.

Laura Case Sherry, whom the New York Times called “the guiding spirit” of the Wisconsin Players,2 had experienced the theatre from both sides — big and little, commercial and amateur. Born in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, in 1876, Laura Case’s parents were Emily Avery and Lawrence Case, owner of the small town’s leading general store. Her parents’ position afforded Laura an education at the University of Wisconsin and the school of speech at Northwestern University. From there she went to study theatre in Chicago and at last New York, where in 1897 she joined the Richard Mansfield Company as an actress and toured the country as a cast member in several plays, including Mansfield’s famous production of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.3 Mansfield, then an opponent of the Theatrical Syndicate, spoke frequently against its stranglehold on the stage, even assailing syndicate bosses inside their own theatres.4 Though Mansfield’s own self-interest later led him to soften his resistance, his early opposition to the centralized commercial theatre must have made an impression on young Laura Case.

At the start of the twentieth century, Case settled back into Wisconsin life. She married Edward P. Sherry, a lumber and paper tycoon from Neenah, and the couple made a home in Milwaukee. There, Mrs. Sherry set to work gathering a club of like-minded theatre devotees and performers.5 The group held meetings and rehearsals in the homes of members, and on April 21, 1909, the amateur troupe staged the one-act Irish drama Riders to the Sea by John Millington Synge at the Davidson Theater in Milwaukee.6 The Irish play was fitting, for the Little Theatre movement in America would draw much of its inspiration from a tour of the United States by the Irish Players in 1911 — but Sherry’s troupe performed Riders to the Sea years before the Irish Players’ visit, demonstrating their foundational role among the nation’s community theaters.7

The nascent Milwaukee association soon gained the support of University of Wisconsin English professor Thomas Dickinson. Unable to produce plays at the university in a time when theatre was not deemed a proper academic subject, Dickinson founded the Wisconsin Dramatic Society in Madison in 1910 and organized a company of players by 1911.8 Dickinson and the Madison group worked closely with Sherry and her Milwaukee compatriots from the start, so that the two associations quickly became branches unified in a statewide society.9 The Wisconsin Players had now been born in earnest.